Farmers in many parts of India face wild swings in rain and heat. Extreme weather events can wash away seasonal crops, leaving rural households in trouble. Indian government data shows 33.9 million hectares of land went under water or excess rain from 2015 to 2021.

Rising Climate Risks in Indian Agriculture

In Mandsaur district, farmers watch monsoon crops wilt under surprise heat waves, as Sentinel-2 imagery spots soil moisture plummet. The Centre for Science and Environment warns storms strike more often in climate-vulnerable districts, and Atlas of Disasters maps show rising losses for rural households.

Impact of extreme weather events on crop yields

Farmers lost 33.9 million hectares of cropped land between 2015 and 2021 to floods and excess rains. Floods, drought and heat waves cut rice and sorghum yields. A report from the centre for science and environment (CSE) lists more extreme weather events in exposed zones.

Those storms smash fields in monsoon season, turning healthy shoots to mush. Villages in central India feel swings from deluge to drought within weeks, shaking food security and rural households.

State-backed crop insurance schemes struggle to keep pace with growing claims. India’s farm insurance saw a spike in insurance payouts after heavy rains across climate-vulnerable districts.

Vulnerable farmers wait for delayed checks, so many skip coverage. The atlas of disasters shows more storms since 2000, driving up demand for crop insurance. Rural families now eye subsidised insurance as a shield against sky-high risks.

Regional disparities in climate vulnerability

Central India’s Mandsaur district faces severe droughts. Flash floods sweep through the Western Ghats. Monsoon crops struggle beneath heavy rains. India lost 33.9 million hectares of cropped area between 2015 and 2021 to floods and excess rains.

These patterns reflect the effects of climate change on agriculture. CSE’s atlas of disasters tracks dozens of climate-vulnerable districts. It highlights spots where extreme weather events hit hardest.

Each region steers demand for india’s farm insurance in its own way. Vulnerable farmers in drought belts pay more for subsidised insurance. Coastal belts seek payouts from agricultural land insurance after cyclones shred fields.

Rainfed rice farms shun pricey premiums. Crop insurance schemes struggle to match patchwork risks across zones.

Increasing Demand for Crop Insurance

Farmers flock to subsidized insurance schemes, chasing timely payouts and a safety net for drought‑hit fields. Space imagery and machine learning models speed up claim checks, so paddies and mango orchards get help fast.

Growing awareness among farmers

Losses stacked up fast after extreme weather events. Government stats show India lost 33.9 million ha to floods and excess rains from 2015 to 2021. This stark data reflects the impact of climate change on agriculture.

The centre for science and environment (CSE) spread maps in open access, cutting through jargon. Atlas of disasters maps became a household reference. Villagers passed them around at tea stalls, pointing to monsoon crops at risk.

Co-op leaders held chats on subsidised insurance in a district in Madhya Pradesh. Villagers heard about india’s farm insurance, the world’s largest plan for vulnerable farmers.

Enthusiasts praised easier claim processes and steady insurance payouts. A young grower used indian government data to set cover levels, chatting on a mobile app. Local groups host workshops on adaptation to climate change.

Government-subsidized insurance schemes

Farmers in India turn to subsidised insurance to shield crops from climate change and extreme weather events. Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana launched in 2016. The scheme covers premium rates of 2 percent for kharif and 1.5 percent for rabi crops.

Governments share remaining costs to ease burden on rural households. The plan uses a weather-based index model and weather stations to trigger payouts. Mandsaur district saw swift insurance payouts after excess rains in 2019.

Indian government data shows India lost 33.9 million hectares of monsoon crops between 2015 and 2021 due to floods and excess rains.

Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reports show climate-vulnerable districts need more coverage. This crop insurance scheme underwrites agricultural land insurance for vulnerable farmers across those areas.

It cuts risk with risk pooling and premium subsidy from the state and centre, boosting food security. Satellite imagery and mobile apps speed up claim settlement. Data from web of science and atlas of disasters helped refine policy.

Smallholders still face gaps in coverage and delayed payouts in some regions.

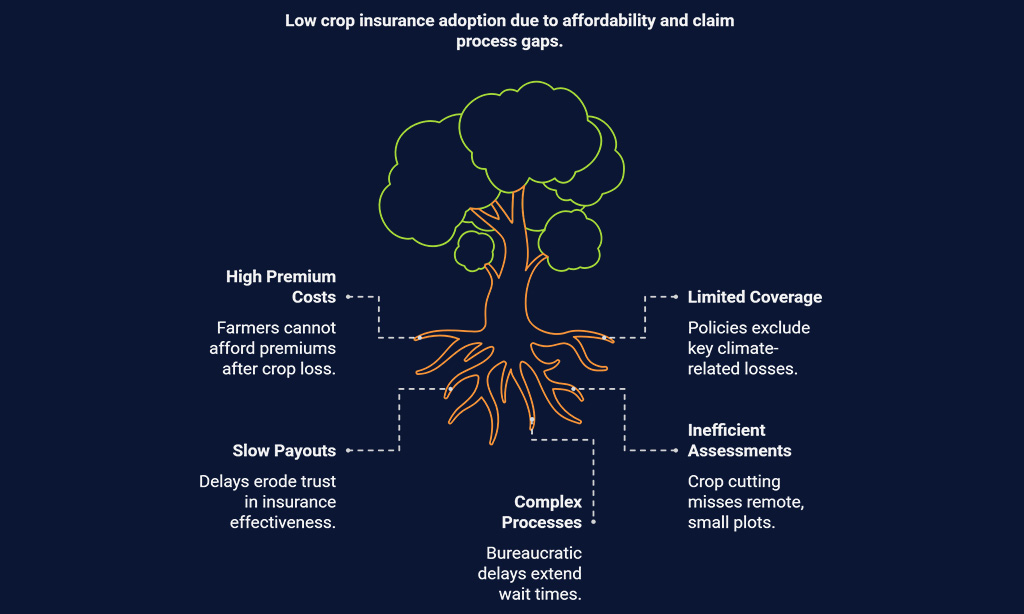

Challenges in Crop Insurance Adoption

Small and marginal farmers often skip premium payments after a bad crop. They face tight budgets, rigid policy terms, and slow payouts, and rural households get lost without simple mobile apps; CSE studies and Indian government data both report these gaps.

Affordability for small and marginal farmers

Farmers with less than two hectares pay up to 20% of the premium under Prime Minister Crop Insurance Plan. That scheme covers floods and extreme weather events like excess rain that wiped out 33.9 million hectares between 2015 and 2021.

Many in Mandsaur district skip it because they lack spare cash. The atlas of disasters flags over 100 climate-vulnerable districts, yet high costs block coverage for monsoon crops.

Insurers set flat rates that rural households find high, even after subsidies. The Centre for Science and Environment study labels India’s farm insurance the world’s largest, yet it leaves vulnerable farmers exposed.

Low-income growers in Odisha and Bihar miss payouts for months, raising doubt about payout speed. Hard cash needs force many to avoid cover altogether.

Gaps in policy coverage and claim processes

Policies often exclude losses from uneven rains or heat waves in climate-vulnerable districts. Mandsaur district saw severe yield cuts after floods, yet many claims failed under the crop insurance scheme.

Atlas of Disasters records show India lost 33.9 million hectares of cropped area from 2015 to 2021 to extreme weather events. Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana covers only defined perils, leaving vulnerable farmers unprotected against climate change threats.

Claim teams use crop cutting experiments to set insurance payouts, but they miss small plots on remote farms. Bureaucratic delays extend wait times for rural households in climate-vulnerable districts, and some wait over six months.

Centre for Science and Environment flagged this issue after a systematic review of claim files. Indexed payments could speed payouts with satellite imagery, yet slow checks hamper compliance.

Subsidised insurance still falls short, so many skip renewals and lose cover. Smallholders chase payouts like shadows, yet funds stay out of reach.

Technological Solutions for Climate-Resilient Insurance

Farmers now tap satellite data and AI to spot risks before storms hit, it feels like carrying a weather guide in your pocket. A simple mobile app lets a farmer file a claim in minutes, saving time for tea and tall tales.

Use of satellite data and AI for risk assessment

Satellite eyes in the sky scan fields all day, tracking effects of climate change. Remote sensing tools from NASA, ESA and ISRO feed models in real time. Index-based insurance flags crop loss for crop insurance schemes.

This model adds speed to india’s farm insurance payouts under subsidised insurance. CSE uses its atlas of disasters and indian government data to map climate-vulnerable districts, from Mandsaur district to coastal belts.

Machine learning spots patterns in monsoon crops and extreme weather events. AI algorithms predict risks before storms hit rural households. The system fed data on 33.9 million lost hectares from floods and excess rains between 2015 and 2021.

It helps insurers set fair premiums for vulnerable farmers. Better risk maps guard food security and back adaptations that save crops. One farmer in Mandsaur cheers, “It saved my harvest”.

Source - https://editorialge.com